|

|

This page was last modified 2024-01-21

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

heath - some thoughts on the word

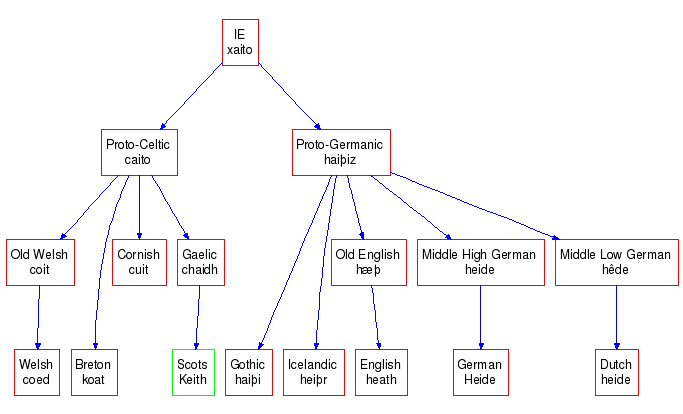

As someone called Keith, living in a heath, I naturally want to understand the connection between those two words. Although in theory everything known is in the standard dictionaries and reference books, in practice each source gives only a small part of the story. So here is my synthesis of the most important pieces. This word family exists only in Celtic and Germanic. I think we can exclude the Latin bucetum 'cow-pasture' sometimes mentioned in this context. Though clearly formed from root bo- 'cow', the suffix is explained by Ernout & Meillet as formed on the pattern of iuncetum 'reed-bed', where the suffix is -etum, not -cetum. We are left to deal with descendants of a word of the form caito, which might be independently inherited from IE, in which case the IE form probably would have started χ- (written x- in the diagram above), or borrowed from one to the other language group; if the latter is the case, from Celtic to Germanic seems more likely. The original meaning would be 'wood' or 'forest', but the meanings later fluctuate and can include 'open land'. These shifts to apparently widely varying meanings are typical of such landscape words and can be explained by cultural factors. The earliest mention of our word appears to be Ptolemy's Καιτοβριχ (Caitobrix) 'wood-hill' (or perhaps 'wood-bridge') in Portugal, now Setúbal. The word (with shift of the diphthong /ai/ to /e:/) is seemingly common in French place-names of Gaulish origin such as Sancy<*seno-ceto(n?) 'old-wood', but these are slightly doubtful as a Latin termination -acum might be involved. It also occurs in Latinized personal names such as Cetius. We are on safer territory in the British isles (and Brittany), where descendants of caito live on in modern Celtic: Old Welsh coit, Modern Welsh coed, Breton koat, Cornish cuit. These form part of many place-names (sometimes with soft mutation, like Welsh hengoed 'old wood'). I am not sure if a Gaelic form survives, but if so, it must be something like chaidh. From such a form derives the name of the town of Keith, hence the family name and later the first name. (There is an alternative possibility from the name Mac Cáidh which I will discuss more later.) The Germanic group appears to start from a form haiþiz, which was feminine, to judge by the gender of its descendants. (Here þ is an unvoiced dental fricative.) Hence Gothic haiþi 'field', (only attested in the declined forms haiþjai dative and haiþjôs genitive), Old Icelandic heiþr and Old English hæþ (long vowel) 'heath', and modern German Heide. There was apparently a variant hāþ (neuter) in OE, giving such names as Hoad in Kent and Sussex. As an peculiar offshoot we get 'heathen', a country-dwelling, unsophisticated and irreligious person. I am proud to be a heathen in precisely two of these senses. From here we get German names such as Haydn (unless this is a short form of Heidenrich). See [KEW] for more on German Heide. The OED definition of 'heath' is "Open uncultivated ground; an extensive tract of waste land; a wilderness; now chiefly applied to a bare, more or less flat, tract of land, naturally clothed with low herbage and dwarf shrubs, esp. with the shrubby plants known as heath, heather or ling". We thus get place-names such as Hatfield 'heath-field'. This compound occurs early: the OED cites "778 Charter in Birch Cartul. Saxon. I. 315 Et eodem septo to hadfeld geate. et eodem septo to baggan gete", and there are several other examples in Bosworth-Toller. It is the name of the street in which I live. We also have to reckon with an early (Jackson thinks before 600) borrowing from British into English, which appears (often disguised) in many place-names, such as Lichfield, Chute, Chittoe, Melchet, Chatham, etc. If this word had survived into modern English, it would have become *chet. For more examples see [LPN], pp. 223-4. references

|